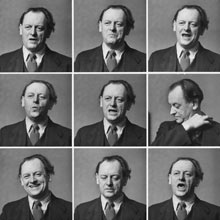

Kurt Schwitters: the modernist master in exile

The German artist Kurt Schwitters lived out his final years in postwar Cumbria, working feverishly in a draughty old barn, poor, hungry and ignored. As the great dadaist and pioneer of pop art finally receives his due in a major Tate retrospective, we travel to the Lake District, on the trail of his final masterpiece and his extraordinary story

Kurt Schwitters in front of the Merz Barn in Cumbria, accompanied by fellow artist-in-exile Hilde Goldschmidt, 1947. Photograph: Sprengel Archive, Hanover/ Littoral

The only known photograph of the German artist Kurt Schwitters at the place where he worked against all the odds on what he hoped would be his final masterpiece – the Merz Barn at Elterwater, near Ambleside – was taken some time in 1946, and almost every aspect of it seems designed to mislead. For one thing, there is the weather, which is idyllic, sunshine falling on the fells like a blessing. For another, there is Schwitters himself, who looks, in his worsted suit and tie, more like a Manchester brewer up for the weekend than an artist in search of a studio. He even has company, in the form of his friend the painter Hilde Goldschmidt, a fellow refugee from Nazi Germany, jaunty in a short-sleeved dress and wide-brimmed hat. All they need to complete the lie is a bulging picnic basket and a beck-chilled bottle of dandelion and burdock.

A more truthful photograph, I think to myself as I arrive at Elterwater, would have caught Schwitters on a day much like this one: barely above freezing, snow on the ground, driving sleet. He would have been inside the barn, not mooning around outside it, and he would have been swaddled, tramp-like, in as many layers of wool and tweed as he possessed, a beret pulled tight over his ears. His trousers would have been spattered with cement, his shoulders dusted with plaster. Hilde, of course, would have been safely at home by the fire. In a way, then, you could say I've been quite lucky with the weather today. "It's useful, actually," says Ian Hunter, one of the co-directors of the Littoral Trust, the organisation which takes care of the Merz Barn. "It helps you to imagine what it would have been like for Schwitters." He looks at my face, and laughs. "Though it is bloody cold, I'll grant you that."

The Merz Barn, remote, dilapidated and mostly forgotten, stands as a perfect metaphor for the life and reputation of the man who once worked inside it. Kurt Schwitters is an artist's artist, influential and revered. A key figure of dadaism, he made some of the 20th century's most beautiful and accomplished collages, and in doing so paved the way for pop art and arte povera. Yet in Britain, the country that sheltered him for the last eight years of his life, he remains a kind of secret, stubbornly and – some might say – unaccountably obscured from view. Even the art lovers who parade through Brantwood, the house where Ruskin went mad at nearby Coniston, tend not to have this shrine on their itineraries – for all that, in its own way, it is just as haunting.

As Hunter is the first to admit, inside there is nothing much to see: Schwitters died in January 1948, having worked on his final project for just three months, and the only section of what he envisaged as a kind of modernist grotto, its walls thick with sculpture and found objects, was removed for safekeeping to the Hatton Gallery, in Newcastle, in 1965. But the atmosphere, gloomy and hunkered, works on you all the same. He slaved like a demon in this place; he had spent the summer of 1947 in bed, having suffered some kind of haemorrhage, and he knew his time was running out. His fingers would have been sore with chilblains, and his feet would have ached. When the weather is bad the barn is prone to flooding, so he was often standing in cold water. He would sometimes have been hungry, too. Schwitters was pitifully poor; at the Abbot Hall Art Gallery in Kendal there is a drawing of Francis O'Neill, the owner of an Ambleside cafe, that he traded for bread.

Hunter points out a few details: a tiny skylight Schwitters had built into a corner of the barn's sloping roof; a lonesome curve of cement. He talks about what the Merz Barn might have looked like had it been completed: an impastoed cavern of false ceilings and stalactite-like protuberances, part folly and part temple. Hunter is, it's fair to say, a Schwitters obsessive. When he first saw the Merzbarn Wall in Newcastle many years ago, he felt it as a revelation. "I had a tangible sense of the legacy of dada," he says. "It was so immediate."

He and his co-director, Celia Larner, arts administrators who had long dreamed of finding a way to build the legacy of Schwitters, finally managed to get their hands on the barn when, in 2006, the grandson of Harry Pierce, the landscape gardener who owned it in the 1940s, offered to sell it to them. (Having promised the artist he would preserve its contents after his death, it was Pierce who donated the wall to the Hatton in exchange, so the story goes, for a bottle of champagne.) "It was crazy money for us but we knew we had to find a way," says Larner. In the end they were funded by the Northern Rock Foundation, and Damien Hirst, who claims Schwitters as an influence.

Since then they've run it as a study centre, a place for artists and students to visit for inspiration. But the going is tough. They're not getting any younger, and in 2011 Arts Council England cut its £37,000 grant completely. At the moment they're maintaining the barn out of their own pockets, and though they're ready to do this – their devotion to Schwitters is so intense, they've even launched a slightly barmy campaign to persuade the Home Office to give him a posthumous British passport – they're baffled it should be necessary.

"This is a place of pilgrimage," Hunter says. "People are always jumping over the wall. But it's also a site of national significance, and it should be embraced by the arts establishment as such. First, Schwitters was there in Germany, 1918, at the beginning of dada; he hotwires us straight into European modernism. Second, it's about honouring his wishes. He wanted his Merz Barn to be preserved. He said: it will be 60 years before people understand who I am. Well, bingo. We're into the 63rd year now."

Their hope is that help may soon come via Tate Britain, where the first major exhibition of Schwitters's late work will shortly open – a landmark for which they can claim at least a little of the credit (when Nicholas Serota, the Tate's director, asked what he could do to help their cause, they told him: we need a show; there had not been a major retrospective since 1985). If the exhibition makes people grasp his importance, their thinking goes, it will be easier to raise money. "Schwitters's influence is quite remarkable," says Hunter. "He's like a thread running through British art from Richard Hamilton on."

He's right about this, though why stop at British art? Who else do the 50s "combines" of the great American artist Robert Rauschenberg, call to mind but Schwitters? (After seeing an exhibition of Schwitters's work in 1959, Rauschenberg said: "I felt like he made it all just for me.") On the other hand, Schwitters doesn't need starry associations to bolster him. He can speak for himself. First of all, there's the work. The best of his collages really are wonderful: deft, and harmonious. The things he can do with a few wooden skittles, a Quality Street wrapper, an old bus ticket! And then there's the life, which is both epic and bizarre, as if he were a creature of myth or fable rather than of a provincial German city. The first time I saw work by Schwitters, a few years ago, it was on the back stairs at Abbot Hall, where I was hanging out, waiting for the rain to stop. A note beside it explained who the artist was, and how he had come to end his days in penury in the Lake District. I still remember my amazement: the idea that an important modernist painter had once won the annual Ambleside flower painting competition. If you made such a thing up, no one would believe you.

Kurt Schwitters was born in Hanover in 1887, the only child of Henriette and Edward Schwitters, a prosperous couple whose income came from property. His career as an artist started straightforwardly: he studied art at the Dresden Academy and then returned to Hanover, where he became an expressionist painter. With the outbreak of the first world war, everything shifted. "Things were in terrible turmoil," he said. "What I had learned at the Academy was of no use to me… Everything had broken down and new things had to be made out of the fragments; and this is Merz."

Merz doesn't mean anything: it is a nonsense word (it comes from Commerzbank, an ad for which appears in one of his earliest collages). But after 1918 everything Schwitters made was Merz, whether it was periodical, painting or poem. He was a one-man movement. "The word denotes essentially the combination of all conceivable materials for artistic purposes," he said. "And technically the principle of equal evaluation of the individual materials… A perambulator wheel, wire-netting, string and cotton wool are factors having equal rights with paint." In other words, art could be made from the things most people regarded as rubbish. Almost overnight, he became a collagist.

In Berlin, where his new work was exhibited, Schwitters befriendedHans Arp, and began to contribute to various dadaist publications (he was an extremely keen writer of dadaist poetry, most notably an epic sound poem called Ursonate, which he wrote over the course of 10 years, and liked to perform in public). But he did not become an official member of Berlin Dada; his application to join the group was not accepted. Not that this disheartened him. In 1920 he began work on a series of Merz Columns – and it was these structures that were to be the inspiration for what is widely regarded as his lost masterpiece: the Merzbau, which he built inside the family home in Hanover at Waldhausenstrasse 5, and which was destroyed by the RAF in 1943.

Schwitters began work on the Merzbau in 1923, and finished around 1933, a project that eventually encompassed six rooms of the house. Obviously, he could not invade the parts of the building that were let to tenants, but if his letters are anything to go on, he annexed at least two rooms of his parents' apartment (he shared his own apartment with his wife, Helma, and his son, Ernst). Poor Herr and Frau Schwitters. Did he warn them, or did he simply present them with a fait accompli? ("Mutti! Papa! Come in! I've just rearranged your sitting room a little…") Because his alterations were nothing if not dramatic. At the Sprengel Museum in Hanover, home of the vast Schwitters archive, there is a reconstruction of the Merzbau, based on the three extant photographs of it – and it gives the visitor a powerful sense of what the original must have been like. White and angular, it is quite fantastical; you feel, at first, as if you have fallen down a crevasse.

The walls have disappeared behind constructions which comprise a series of grottoes, columns, shelves and cubes. On one column is a death mask of Schwitters's first son, Gerd, who died as a baby; the grottoes, meanwhile, were themed, some dedicated to colleagues such as Mondrian and Arp, another to Goethe, still others to love and war. The effect of all this strange geometry is disorienting and paradoxical. Even as you're beset by a sense that the floor is shrinking and the ceiling growing ever lower, the structure itself seems somehow to be infinite – which is, perhaps, precisely the effect Schwitters was after. During the decade he worked on it, the Merzbau was always changing; he joked that it would grow and grow until it reached Berlin. There was something of the tortoise about Schwitters; like the hoarders you see in Channel 4 documentaries, he was forever building himself a new shell.

Schwitters was by now rather famous in Germany, and he had plenty of work (he had a nice sideline working as Hanover council's official typographer). But circumstances were about to intervene once again. After Hitler's rise to power in 1933, the Nazis were determined to wipe out what they regarded as entartete Kunst, or degenerate art. Schwitters's work was mocked, confiscated and eventually banned, and in January 1937, on hearing that the Gestapo wanted to see him, he fled to Norway. (Ernst was already there; Helma stayed in Hanover to look after their parents). A few months after his escape, Hitler was photographed in front of one of his collages at an exhibition of degenerate art in Munich.

In Norway, Schwitters began work on a second Merzbau: this one would be portable, which rather backs up my tortoise analogy. But in 1940, when the Nazis invaded, he was forced to abandon it, too, and he fled to Edinburgh on the last ship out, an ice breaker called Fridtjof Nansen. When he landed, he had nothing with him but two white mice and a whittled birchwood sculpture. In Britain, however, he was regarded as an enemy alien. He would be interned. There followed stays in various camps until he was finally sent to Douglas, on the Isle of Man, where he would remain until November 1941.

This wasn't, perhaps, quite so bad as it sounds. "By pure chance, Hutchinson Camp was full of artists and intellectuals," says Gretel Hinrichsen, whose husband, Klaus, was interned with Schwitters. "They were the crème de la crème." Klaus, an art historian, ran the camp's "university", as a result of which a sympathetic commander gave him an office. He, in turn, allowed Schwitters to use it as a studio (Schwitters thanked his friend by painting his portrait, a work that will be in the Tate's show). "In a way, they had quite a good time," says Gretel. "They stayed in seaside boarding houses, and they were so like-minded, they got on well. But it wasn't easy to work. [For canvas] they used pieces of wood or lino, anything they could find. They used oil from cans of sardines." She laughs. "My husband had bushy eyebrows, and they used his hairs as brushes."

Since no plaster of paris was available, Schwitters made sculptures from porridge, which would quickly begin to rot. "He collected up what people didn't eat, and he built them in this attic, and they absolutely stank, of course."

After his release, Schwitters made for London, where he tried to scrape a living from portrait commissions and resumed his Merz works. It wasn't easy. Jack Bilbo's Modern Art Gallery gave him a one-man show, for which Herbert Read, the famous critic, provided the catalogue introduction – "a poet parallel to James Joyce", he wrote – but only one collage was sold. Just to add to his misery, it was during this exhibition that he received a telegram informing him that, in Germany, Helma had died of cancer, and the Merzbau, not to mention his home, had been destroyed in a bombing raid.

Then, salvation. There was a young woman – she was half his age – called Edith Thomas, better known as Wantee (Schwitters gave her the nickname because she was always asking him if he wanted tea; she called him Jumbo). The two of them boarded in the same Bayswater house, and when the war finally ended they decided to go to the Lake District for a holiday, a trip they paid for by selling Kurt's stamp collection. Wantee was an ordinary London girl – she worked on the Marks & Spencer switchboard – and she knew nothing of avant-garde art. But she loved Schwitters, and she believed in him, and when it became clear that he liked Ambleside, that he wanted nothing more to stay and work there, she decided to stay with him.

"Oh, she was wonderful," says the critic William Feaver, who knew her towards the end of her life. "I've always felt that there is no point being indignant about how Schwitters was treated. He was odd and disorganised but he was always very content, and he had Wantee. She loved mothering older men. That's just what she was like." Gretel Henrichsen believes that Schwitters would have died years before he did if it hadn't been for her. "She wasn't his nurse. I've seen her described as that, and it's complete rubbish. But she did take care of him. She adored him, you see. She thought the world of him. There wasn't a person she met who she didn't tell about Schwitters. It was the same wherever she went. No taxi driver was safe." Wantee was even able to take Schwitters's magpie tendencies in her stride. She told Feaver that by the time they moved into what would turn out to be their final lodgings in Ambleside, it took a horse and cart to move the pile of rubbish he had amassed; she hid it from their landlord under the bed.

Schwitters loved the Lake District but life there was hard. He and Wantee were very poor – Henrichsen remembers that even the buying of a single apple was a big deal – and some of the locals were stand-offish. They thought this suitcase-carrying fellow (it held his paints, brushes and boards) uncouth, and they didn't understand his work. The two collages – he made hundreds in this period – that he showed at the Lakeland Artists' Exhibition at Grasmere in 1947 did not sell; people preferred the tourist views he would paint and lay out for sale on the steps of Ambleside's Bridge House. No wonder he took such ironic delight in his success at the Ambleside flower show. "I sent six pictures… Mrs Vartis's roses got the first prize and Mr Bickerstaff's Chrisanthemum [sic] the second. So I got two prizes. The only thing is that the prizes are low 1½ gns. But the honour! People here know now that I am able to paint flowers."

Things were about to get even more difficult. In October 1946 Schwitters fell and broke his leg, an accident from which he would never fully recover. His time now became doubly precious, and he began to look around for a new site on which to construct one final masterpiece. Harry Pierce, a talented landscape architect, lived at Cylinders Farm in Elterwater, where he was planting an extraordinary hillside garden on the site of an old gunpowder works, and Schwitters, who had been commissioned to paint his portrait, was much taken with his methods: "He lets the weeds grow but makes it into a composition merely by adding some small touches. Exactly like I make art from rubbish." He asked Harry if he might have available a barn or shed in which he could work.

In June 1947 Schwitters finally received some good news: he had been awarded a fellowship by the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and this would fund the sculpture he would create inside Harry's old hayloft. The project would take three years but it would be worth it. He believed it would one day be considered a "Lakeland monument". And so, that autumn, he began. "He went to work with feverish energy," Pierce recalled later. "His eagerness and enthusiasm got the better of his weakness until it was barely noticeable." But the sand was running through the hourglass. He spent just three months on his third and final Merzbau. In the cold and damp, he developed bronchitis, which turned to pneumonia. He died, aged 60, in Kendal Infirmary on 8 January, 1948. A letter informing him that his application for British citizenship had been successful arrived two days later.

It's a sign of how Schwitters's reputation has gone up and down over the years that the institution which will shortly stage a major show of his work turned down the opportunity to become the home of the Merz Barn wall when it was offered the fragment in 1962. "Yes, the Tate turned it down on the grounds that it was impossible to move," says Fred Brookes. "But being the kind of guy he was, Kenneth Rowntree [the then professor of art at Newcastle University, the home of the Hatton Gallery] simply said to Mr Pierce: 'My dear chap, we'd be delighted,' and no questions asked."

Brookes, now a cultural strategist, has had a long and extraordinary relationship with the Merz Wall. In 1965, when he was a second-year art student at Newcastle, the artist Richard Hamilton, who was one of his lecturers, asked him to join the team which would survey the wall, now rapidly decaying, before it was moved to the Hatton. (It was Hamilton who had "rediscovered" the wall, and he was the prime architect of the move, at least initially.) "I was good at measured drawings, so I had to map it all in case any bits fell off. In the end I think I spent longer with it than Schwitters did." Does he remember the first time he saw it? "Oh, yes. Very well. It was a sunny day, and it was just… hanging there in the dark. It was quite stirring."

Brookes was there, too, during the move itself, the university having dispatched this keen young undergraduate to look after the wall's interests while it was in the care of the contractors. It was all a bit Heath Robinson. Before it could be removed, the slate wall had to be backed with steel and concrete so it could be lowered on to the van in one piece; in the end, the thing weighed 15 tons. "The Carlisle contractors were fantastic," he says. "They treated it with tremendous respect. But then Pickfords moved in – they sent a team that specialised in moving electrical transformers across fields – and it was just this big lump to them. At one point they were winching it up and it wasn't quite straight. I saw this guy pick up a sledgehammer to tap it into line, and I just flung myself between him and it. In the end, though, it arrived in Newcastle in as good – by which I mean, as bad – a state as it was when it left the barn."

Brookes believes that the Merz Wall loses a lot in translation, and he longs for the Hatton Gallery to build a new barn around it, the better that people might experience it as its creator intended. Is he right about this? I'm not sure. At Elterwater, Hunter and Larner feed me tea and hot soup, and then I return to Kendal, where I get the train across the Pennines to Newcastle; the Wall, for obvious reasons, will not be travelling to the Tate, and I don't feel I can write about Schwitters's exile in Britain without seeing it.

So, the end of my own pilgrimage. It's true that the gallery atmosphere works to reduce its drama: where there should be a dirt floor there is parquet; where there should be shadows there are spotlights. But still. Being able to see it properly enables you to take in the achievement of it all. The way he allowed the contours of the wall to dictate the mounds and depressions he sculpted over it. The subtle contrasts between different colours and textures. The oddness – and poignancy – of the found objects nestling in its hollows: the spout of a child's watering can, a three-pronged slate splitter, a length of brown string, a china egg. It has a weird, primitive grandeur: part cave painting, part modernist fantasia.

What strikes me most of all, though, is its overriding hopefulness. In its nooks and crannies, I grant you, there is a feeling of death, of bomb sites and memorial places. But when you stand back, it seems airy and weightless, more of a wave than a wall. As Rob Airey, the Hatton's keeper of art, points out to me, its trajectory is upwards and to the right – towards what would have been, when it was in the barn, a tiny window. It's amazing, this, when you think about the plight of the man who made it. Schwitters was poor and ignored; he was cold and hungry; he was dying. And yet his final work, for all that it is only a fragment, seems always to be moving effortlessly towards the light.

Schwitters in Britain is at Tate Britain from 30 January to 12 May

Source: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2013/jan/06/kurt-schwitters-modernist-master-exile

There is a fantastic collection of Spencer's in the Imperial War Museum London, from his time as a War Artist during World War I. Definitely worth a visit if in London or check out their collection on line. I think that if I 'did a Schwitter's', I would end up wearing the wall as a face mask! lol

ReplyDelete